As I was writing this post, I realized that I didn’t have a category for mollusks…a somewhat understandable oversight for a blog historically focused on West and Central Texas. Oyster beds and clambakes are few and far between. I’ve remedied that situation by changing the “Wildlife — Insects” category to “Wildlife — Invertebrates,” trusting that grasshoppers won’t be overly offended by their association with crawdads.

It’s probably a bit too early to proclaim the end of the drought that’s been gripping the state for months, but the plentiful rainfall we’ve received over the past few weeks has certainly revived the landscape, even if it’s failed to raise lake levels very much, or allow creeks to flow again.

A few days before the rains returned, I did some exploration of Pecan Creek, a portion of which runs behind our house. The creek had stopped flowing in May, resumed its flow briefly after an isolated downpour in June, and stopped again shortly thereafter (and is still not flowing as of the date of this post).

I had never seen the creek bed completely devoid of water, and I wanted to document it because…well…that’s just what I do.

In the past, this section had standing water even during brief times when the creek didn’t flow.

The bare creek bed did expose some puzzling things.

Nestled amongst the rocks and pebbles were literally thousands of empty shells, remnants of unknown — to me, anyway — bivalves.

Although I found this very interesting, I didn’t think to pursue it further. But a few days later, we were finally blessed with some beneficial, heavy rainfall, and while walking on the low water crossing a block from our house, Debbie and I noticed that a pair of shells had washed up onto the concrete apron. This time, my curiosity was piqued enough to try to identify what creatures once called these shells home.

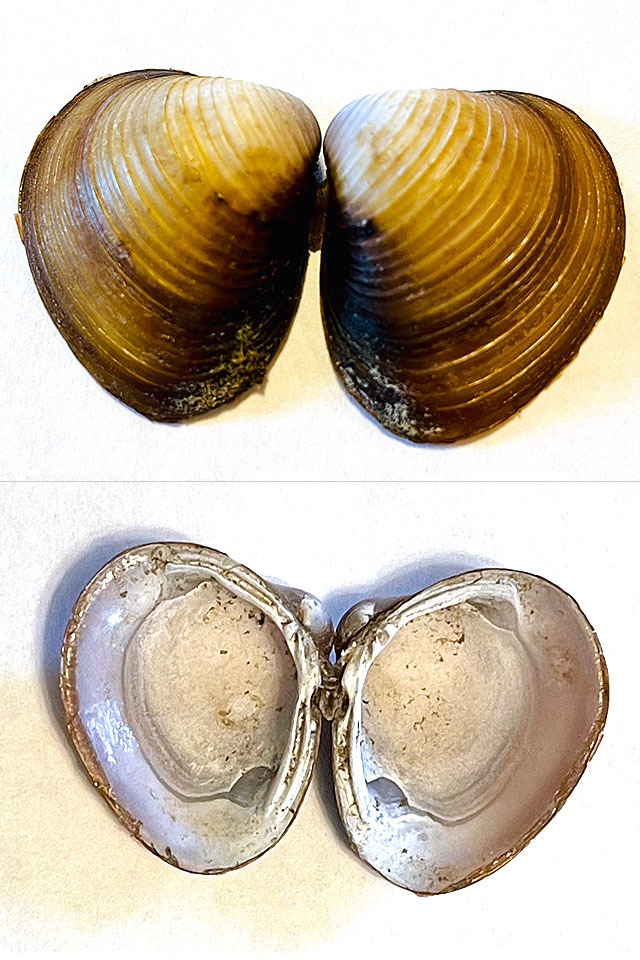

Here are a couple of photographs of the shells (the first is to give a sense of their size).

I began my search with the idea that these might be freshwater mussels. I was pretty confident that these weren’t the terribly invasive and destructive zebra mussels, but to confirm that I found the Texas Parks & Wildlife’s Texas Mussel Watch website. Between that site and a Google image search, I landed on an ID of Utterbackiana suborbiculata, aka the Flat Floater mussel.

I then uploaded the bottom photo shown above to iNaturalist, along with my preliminary ID…and I was quickly corrected by people who knew more than me, i.e. everybody. As it turns out, these shells belong to the Asian clam* (Corbicula fluminea), an invasive (and potentially destructive) species of mollusk that is common in Texas, as well as many other parts of the country. In fact, according to the Texas Invasive Species Institute (see preceding link), Asian clams are:

Currently found in the following Riverways: Angelina, Colorado, Rio Grande, Guadalupe, San Antonio, San Jacinto, Sabine, Red, White, and Brazos drainages; the Clear and West Forks of the Trinity River.

The two bolded riverways flow through our part of Central Texas. However, Pecan Creek is isolated from both, so it’s still a mystery to me as to how the Asian clams came to infest it.

If you’re unfamiliar with iNaturalist, I can’t recommend it highly enough as a resource for identifying flora and fauna of any species and in any location. You can use the website on your desktop, but the app for a mobile device is where the real payoff comes as you can take a photo and immediately upload it to iNaturalist for identification or confirmation. In addition, when you do this, you’re adding to the crowd-sourced knowledge database that can be accessed worldwide. The links for downloading the free mobile apps for Apple and Android devices may be found on the iNaturalist home page.

I mentioned above that the Asian clam is “potentially destructive.” While it’s not known to be as harmful as the zebra mussel, it has been shown to “biofoul” power plants, where it can clog the piping when water is drawn from a lake or river for cooling purposes. Pecan Creek does empty into Lake LBJ upstream from the Thomas C. Ferguson Power Plant. I’m unaware of any reports of problems caused by Asian clams. However, the lake is now home to a population of zebra mussels and the same steps that help mitigate their spread and damage should also work for Asian clams.

By the way, the dry creek bed shown in the first photo above is once again graced with a trickle of water. We still need another six inches of rain or so to get enough runoff to recharge the spring and jumpstart the creek to its usual animated state, but we’re breathing a sigh of relief for now.

*Had I been a bit more diligent in my initial research, I would have known that the flat floater ID was incorrect, as that mussel grows to 7″ or more…much larger than the Asian clam.

Discover more from The Fire Ant Gazette

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.