As they marched us back from the river, one soldier was carrying an American flag. That flag was a beautiful sight. I wish that flag could have the same meaning to everyone in this country now.

— Loy Dean Lawler

Dr. Loy Dean Lawler was an optometrist who practiced for many years in Mount Pleasant, Texas. He was my wife’s uncle (well, the relationship is a bit more complicated than that, but it will suffice). Loy Dean passed away in 2010 at age 86, a well-respected and devout gentleman.

He was also an Army veteran who was awarded two Purple Hearts and the Bronze Star. He endured four months as a prisoner of war, captured by the Germans along with thousands of his fellow American soldiers following the Battle of the Bulge.

In 1995, after returning from a reunion of the 106th Infantry Division (the first and only such reunion he could bring himself to attend), Dr. Lawler wrote his memoir of that ordeal. What follows is sometimes hard to read, but perhaps even harder for those of us raised in security and freedom to relate to. It’s a stark reminder of the sacrifices that those who came before made so that we can enjoy that security and freedom. It’s difficult to know exactly how to express gratitude for these sacrifices, but the least we can do is…never forget.

POW Experience

Dr. Loy Dean Lawler, Mount Pleasant, Texas

I was captured near Schoenberg close to the German border about 4:00 P.M. on December 19, 1944. I was with the 106th Infantry Division, 423rd Infantry Regiment, 2nd Battalion, Company E, 1st Platoon. Captain Maxey Crews was our company commander. We had 4 or 5 left out of our platoon. The rest were killed, wounded, or simply missing. We had not had food or been warm or dry since the morning of December 16th.

At the time of our capture I was with Captain Crews near the dugout that I supposed could be called the Regimental Headquarters. I can still see the anguish and tears on Colonel [Charles C.] Cavender’s face when he came out and said we were going to surrender.

I can truthfully say nobody around me wanted to surrender. Captain Crews had me relay the order to cease firing and to destroy our weapons. I thought some of the guys were going to shoot me when I passed the order on. It was a problem to get everyone to quit firing. There was some firing after I destroyed my M1 rifle, and that did make me nervous, being without my M1

We were marched out of the woods and into an open field. On our way I was nearly shot by an SS trooper when I refused to let him have my watch. I changed my mind real quick when he drew his sidearm and put it in my face. I realized later how stupid I had been. The next thing was to destroy a pen and pencil set my Mother had given me, just to keep them from getting it. We huddled together in this open field the rest of the night. Early next morning we began a march that lasted all that day and the following night. I think we went to Prum and onto Gerolstein, but am not sure. The morning of December 21st we were given a piece of bread and put in boxcars. There were 60 of us in one boxcar. It had wooden benches where some sat, and the rest had to lay underneath the benches on the hard and cold floor.

We had several that were sick or wounded and lot of the men had diarrhea. Some were so weak they simply relieved themselves in their pants. Others hollered for the helmet that was passed around and emptied through a hole in the boxcar. I didn’t think until later that I hope that wasn’t the same helmet that was used to give us water. There was a stove in the boxcar, but nothing to burn–it was just in the way.

Our train was pulled onto a railroad siding in Limburg, near Frankfurt, to allow higher priority trains to move on. On the night of about December 23, we were bombed by the British. It was quite a show with all the flares and earth-shaking explosions.

We managed to get out of the boxcar. I remembered seeing a foxhole earlier that was nearby. I ran for that and jumped in with the bombs exploding. I jumped on the back of a German guard that was already in the one-man hole. I quickly pushed him back down as he tried to get up and made a fast exit. We had hopes of escaping, but were quickly rounded up after the bombing ceased. I am not sure of this, but I was told we lost 12 out of our 60 men–to the bombs and by the guards thinking some were trying to escape. One of those killed was a friend who had married the day before we left to go overseas. His body lay in front of our boxcar all Christmas eve day. A Sgt. McNamara in our group was a good singer. He was leading us in Christmas carols when the bombing started.

We stayed in the boxcar about 10 days. During that time we had 1/6th of a Red Cross parcel and water once or twice. I am a little hazy on the water that was scarce, but I know for sure about the few bites of food we received.

We arrived at Stalag IVB about December 30th and was assigned to barracks December 31st. Several of the men were too weak to move and had to be carried off the boxcar. I believe we had one die.

We had to undress and were put in a “gas” chamber and deloused before being given a small bowl of warm oatmeal. That was the best meal I ever had-and the last for several months. While at IVB, we were in bunks (hard planks) that were so close together we could hardly turn over. There was a latrine at the end of the barracks with two barrels outside the door. With so much dysentery, most of us couldn’t wait our turn and had to go in the barrels. Some Poles who had been in the camp a long time would come in and eat the feces out of the barrels when they could find any of a solid nature. We were not that starved yet. Later on I did find myself digging into a cow pile with a stick, looking for something solid. I found a couple of pieces of undigested carrots that were pretty good. Our diet at IVB was watery soup with very little solids.

About the middle of January, 1945, I was transferred to a Russian work camp, arbeit Kommando L71A near Boxwitz, Germany. We were close enough to Dresden to see the lights and the bombing of that city.

I was with a group of 100 Americans and 400 Russians. Thirty-one of us and four Russians were assigned to work 6 days a week, 12 hours a day, in a coal brickette factory in Boxwitz (or Bockwitz). It was called Fabrique Eine und Zwie. We got out of bed at 4:30 in the morning, stood outside in formation for roll call. The guard would hit anyone with their hand in their pockets because it was not soldier-like. This was before daylight. We then walked one hour to work, before the 12-hour workday.

We had no breakfast–only a cup of what I call acorn coffee, barely more than warm water. Our noon meal consisted of half a Klim can of rutabaga soup without the rutabaga. The night meal was the same with a small piece of bread. On Sunday, our day off, we had only one meal, but I believe we got one small potato occasionally. If we found a worm

in our soup that was good–something a little solid. Only on one occasion did we receive 1/6 of a Red Cross parcel, and that was near the time we were liberated.

My work involved some standing on a high scaffold and knocking out a ceiling with heavy hammers. I remember falling once, but wasn’t seriously hurt. This didn’t last very long, and the rest of the time we were working outside-stacking coal brickettes and loading things on boxcars. One day a German soldier, not one of our guards, came by on an inspection tour and told me to take my coat off–in the coldest winter ever recorded in that part of Germany. I refused. He tried to take it off, but finally gave up and moved on. He was so mad he was frothing at the mouth. I kept my coat on.

A woman in a nearby house saw us wrestling around. She came out of the house and hid something under the snow next to a chimney. When no one was looking, I slipped over and found a small piece of cake. I mention this to let everyone know that all Germans were not bad.

The best part of our work was near the end of our captivity when the P-38s would strafe the plant. We would get to go to the bomb shelter. A German civilian worker would occasionally hide a thin slice of bread in his hat band and give it to me in the darkness of the shelter.

Our walk to and from work was rather uneventful–except for the cold. I do remember one time a Russian, while walking in formation, (we marched everywhere–never walked) stepped out of line while urinating to keep from hitting the guy in front and the German guard shot him in the face, the bullet going through both cheeks. He walked on to camp without any help.

There was a place in camp where we could take a shower–like once a week. We were separated from the Russians, but they could cut the hot water off when were in the shower and had fun doing it.

About March of 1945 I began to run a temperature and get weaker and weaker. I no longer could eat and had to give my food away. I worked as long as I could because several of the Russians were shot in bed when they couldn’t get up. I was lucky, for they put me in a horse-drawn, iron-wheeled wagon with the guard, and took me to the nearest railroad station. I had pleurisy and it hurt to even breathe. I was too weak to sit up, so laying on those hard boards in the wagon and going over those cobblestone roads was a real experience.

We boarded a train for a hospital in Lebenwerda, Germany. It was an old theatre building. Our beds were planks that used to have a little straw on them. The British doctor in charge brought a German colonel in to see us. He, with one hand, put his fingers completely around my leg–just about skin and bone. The doctor was bitterly complaining to the Colonel about our condition. The next day I was taken to a regular hospital for X-rays and some other tests, and then returned to our own “hospital.” Soon afterwards, the British doctor received some medicine that broke my fever and I started to get a little better. The guy next to me in the hospital was from the same barracks in our work camp, in fact, slept next to me. He died with something similar. I knew I was in bad shape when they placed this other man and me in the only two beds in our theatre hospital. I weighed 88 lbs and probably lost a little more weight before I got better. I was soon returned to the work camp. It was a strange feeling to travel on a train with German civilians. They looked at me like I was from Mars.

By April the weather began to get a little warmer. Just before we were liberated, as previously mentioned, we received 1/6th of a Red Cross parcel for each man. Prior to this we had no contact with the Red Cross. They “lost” us. About this time we began to miss some of our bread rations and the rutabaga soup without the rutabaga was replaced with some sort of sugar beet soup that was hardly edible. I traded a pack of cigarettes out of the Red Cross parcel for a loaf of bread, but it was stolen before I could eat it. I now know how a person feels when they lose all their worldly possessions.

Sometime after the middle of April all of our guards suddenly disappeared. The exception was a French soldier in German uniform. He was the only decent guard we had. He stayed with us. We could hear firing by the Russians advancing towards us. We started walking towards the American lines to keep from being captured by the Russians and, according to local rumors, marched back into Russia.

We lived off the land–like digging up potato eyes planted in the ground. We found a little burned cheese from a train that had been bombed. Here we were looking into horse and cow manure or anywhere we could find something to eat.

Just before we met the Americans at the Elbe river I was resting by the side of the road when I looked out into a field where a pregnant woman was working. A German guard began stomping her as she lay helpless on the ground. About the same time a German officer sat down beside me and told me the Americans should join up with the Germans and whip Russia while we could. We had spent several days just ahead of the Russians–like getting up (out of a barn) and separating ourselves from the Russians.

In the late afternoon of April 24th we crossed a bombed-out bridge on what I think was the Elbe River and met the Americans–273rd Infantry of the 69th Division. As they marched us back from the river, one soldier was carrying an American flag. That flag was a beautiful sight. I wish that flag could have the same meaning to everyone in this country now. During this walk one of our guys took a bicycle away from a German civilian, but several of us made him give it back. I did get a German officers sabre, but it got bent in the celebration and I threw it away.

We were put in this German home for the night. The man’s wife and daughter left to stay with the neighbors, but the husband stayed with us and tried to celebrate with us. He soon passed out on his bed. I went out and milked his cow and drank the milk immediately. This was better than cognac. Our stomachs couldn’t take anything very strong. The Russians arrived at the Elbe river about an hour after we did, and they were not as nice to the German civilians as we were.

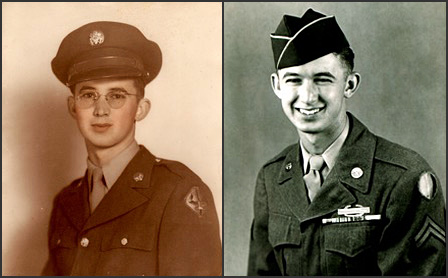

Loy Dean Lawler as a new recruit in the Army Specialized Training Program (left), and as a corporal after his return. He quipped that “any POW who survived got an immediate promotion – some way to get a promotion, huh?”

I don’t remember where (maybe Trebsen, Germany), but the 69th Division took us to some barracks where we were billeted for a few days. During the first night with this I&R platoon, 273rd Infantry, 69th Division, we broke into the mess hall and stole most of their food. We returned most of it later when we found out we couldn’t eat as much as we thought we could.

We were next sent to Camp Lucky Strike in France. After about two weeks and what I then thought was good food, we were put on a Liberty ship on our way back to Newport News, Virginia. A friend of mine, B. J. Carmichael, and I stayed on deck all the time. We never saw our assigned bunks.

This coincidence is worth mentioning. B. J. Carmichael, from Dallas, Texas, and I took our basic training in Camp Wheeler, Georgia. From there we were sent to the University of Alabama under the ASTP. We were still put in the same unit. We were then sent to Camp Atterbury, Indiana, still together. We went overseas to England and France, still together. During the Battle of the Bulge, around St. Vith, we were separated. After we were captured, we were together again. When were put in the boxcars on the way to Stalag IVB, we were together. Out of the thousands at IVB, we were in the same barracks and we both were picked for a group of 100 Americans to go to work in a Russian work camp with 400 Russians. A day or two after I went to this German hospital, here came Carmichael.

We were together until liberated and sent to Camp Lucky Strike. Out of the thousands there, we were still on the same Liberty Ship back to the States. Finally, he was discharged from Ft. Ord, California, and I from Ft. Hood, Texas, but not before we spent a recuperation leave together in Hot Springs, Arkansas.

We haven’t seen much of each other since. It is a shame we haven’t, but I think both of us didn’t care to dwell on the past all that much. He will always be special to me. While the bullets were flying around, I can still hear him hollering for me to “get down.”

To regress a bit, back to the work camp, I twice was put on a detail of about 6 guys to clean out the furnaces at the factory (or plant) where we worked. The ovens looked like pictures I later saw of these ovens where bodies were cremated. This was on a Sunday, supposedly our only day off. The oven doors were just big enough to crawl in, one man to a furnace. While scraping the wall down good, we stood on some grates above a bed of coals that were still hot. We couldn’t stay in the ovens very long at a time. There was enough room for us to fall through the grates, but this was one time everyone was real careful. The only air we got was from the open oven door.

I say all of the above to say this. This wasn’t any worse than having to stand out in the cold snow and ice at the brickette factory 12 hours a day with just a pair of G.I. boots on your feet. G.I. boots are not warm and they are not waterproof. There ought to be a special place in hell for the person who sold the Army those boots. My feet are still cold.

I know I have rambled around a bit and hit a few highlights. After almost 50 years there is no way I can remember everything. To those of you who were there, you can understand.

If you’re interested in learning more about the details of the battle leading up to the capture of American soldiers following the Battle of the Bulge, feel free to check out the following accounts:

- Wikipedia: Battle of St. Vith – The surrender of the Schnee Eifel pocket, 19-21 December 1944

- U.S. Army History (official): The Ardennes – Breakthrough at the Schnee Eifel (esp. pages 166-167)

Many thanks to Loy Dean’s daughter Mercy and his niece Becky for providing access to this story and photos. This has been posted with Mercy’s permission.

I’ve posted this for two reasons. First, it’s a way for me to honor a man with whom I was acquainted for decades, but only recently came to know this chapter of his story. Like so many of his generation, he rarely spoke of his wartime experiences.

Which brings me to the second reason: these veterans are leaving us at an alarming and increasing rate, and with them go the stories that illuminate their lives and educate their descendants. Those stories need to be preserved, and this is one way to do that.

Discover more from The Fire Ant Gazette

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.