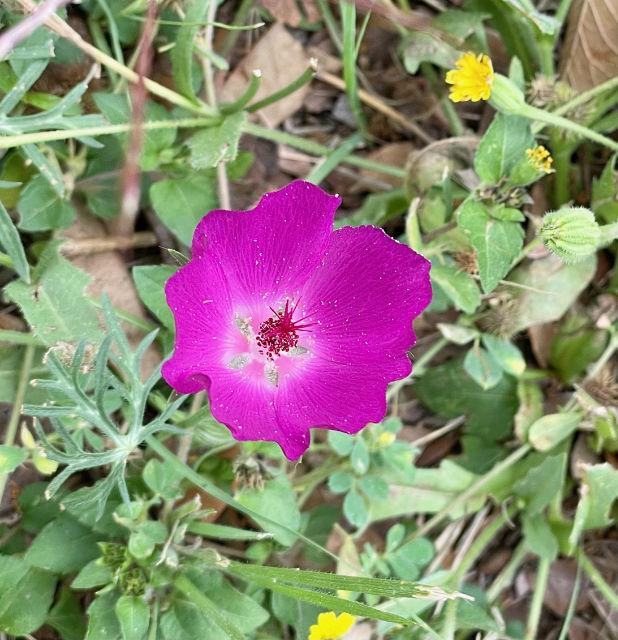

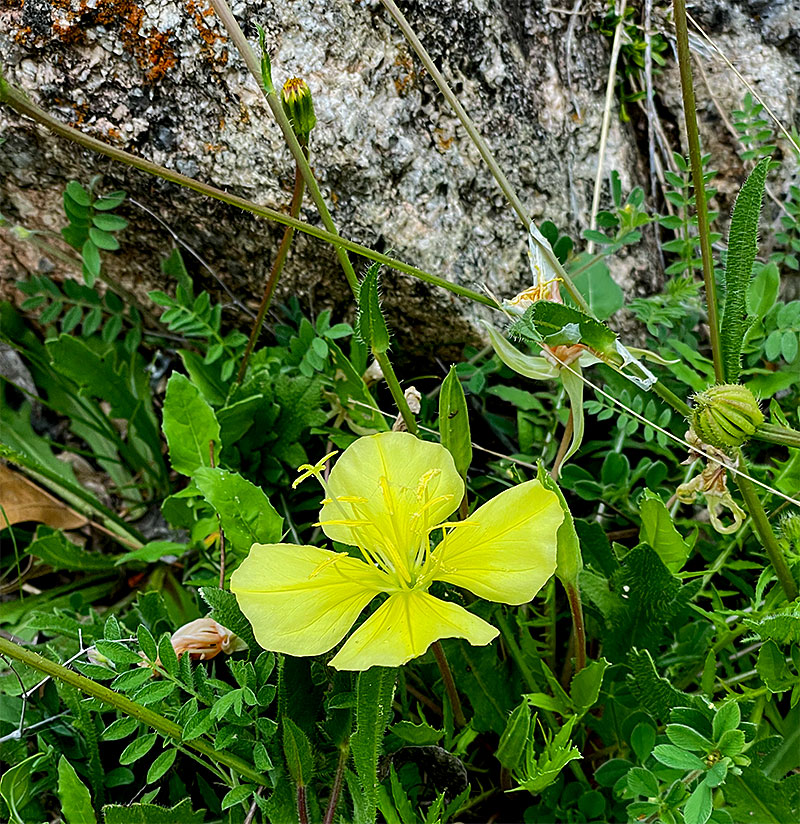

Bluebonnet season is winding down, although there are still a few late bloomers (we can finally use that phrase in the literal sense) enlivening the landscape. But now the color palette is shifting to the longer wavelength end of the spectrum, i.e. the reds (firewheel or Indian blanket), oranges (Indian paintbrush), and yellows (uh…those little yellow flowers). The short end of the color spectrum hasn’t been entirely abandoned thanks to the persistence of winecups.

I realize that most or all of these plants could be considered weeds, especially after they stop blooming, but I kinda like the description provided by the author of this article: the only difference between a wildflower and a weed is our perspective.

If I seem a bit (or a lot) unsure about the identification of some (or all) of these flowers, it’s because I possess only the most rudimentary knowledge about the flora in Central Texas. In fact, I spent way too much time thumbing through a Texas wildflowers field guide in treeware format, which only served to reinforce the value of a good search engine. Here’s a tip for aspiring flower field guide authors: if your table of contents is by the scientific family name in alphabetical order, you’ve lost 90% of your audience right off the bat. I submit to you that anyone who already knows the difference between members of the Fouquieriaceae family and those belonging to the Lentibulariaceae clan doesn’t need a field guide. Instead, arrange your book by flower color. Trust me on this.

In preparation for what we hope is a massive migration of monarch butterflies, milkweed is making its presence known. It’s difficult to overstate the importance of milkweed to the life cycle of monarchs, as the plant provides the sole source of sustenance for monarch larvae (i.e. caterpillars). Here’s a terrific summary of the relationship between plant and butterfly, including an answer to the question, how do they find milkweed to begin with?

There are several species of milkweed, and while a monarch larva isn’t necessarily as picky an eater as, say, your average eight-year-old child, they do seem to prefer some species over others, at least according to this article. OK, that’s not technically accurate; the study in question was actually observing which species of milkweed the female monarchs preferred for egg-laying. I assume that once the eggs hatched, the larvae had little dining choice. Oh…and the answer? Swamp milkweed (Asclepias incarnata) and common milkweed (A. syriaca) averaged the highest number of eggs.

Most of the milkweed in our neighborhood is antelopes horn milkweed (Asclepias asperula); see photo below, taken a few weeks ago.

OK, enough botany. Let’s switch to herpetology, a subject that I’m a bit more familiar with.

Spring in these parts is heralded in part by the Great Turtle Migration (it rivals that of the Monarch butterflies). You might question the motivation for chickens to cross the road, but it’s even more puzzling why turtles want to do that. Well, we know (or think we know) most of their motivation: they’re seeking out just the right spot to dig a nest and lay eggs. But it seems like they traverse perfectly reasonable egg laying landscape in order to venture — very slowly — across busy streets and highways in order to arrive at essentially the exact same terrain on the safe side of the road. What are they thinking?

Anyway, I found this female river cooter on the edge of the street a block from our house last week, and I escorted her to the other side. She wan’t all that appreciative; if you’ve ever picked up a turtle, you know what I’m talking about.

Conventional wisdom tells us to always move a turtle in the same direction it was already headed. If you try to reverse its course, it will just turn around and head back in the original direction once you leave.

But, once nature has been allowed to run its course, absent any flattening by unobservant drivers, here’s the result.

This tiny (possibly newborn?) river cooter was on the sidewalk in front of the gate to our courtyard on Tuesday. I at first mistook it for a green pecan, overlooking the facts that (1) it will be months before there are any pecans on our trees, and (b) green pecans are much less cute and mobile than this.

Debbie and I relocated the tiny critter to the low water crossing and we assume that he found a new home in the creek. Or was eaten by a cottonmouth. Life is tough when you’re a tiny turtle.

Ahead there be serpents…

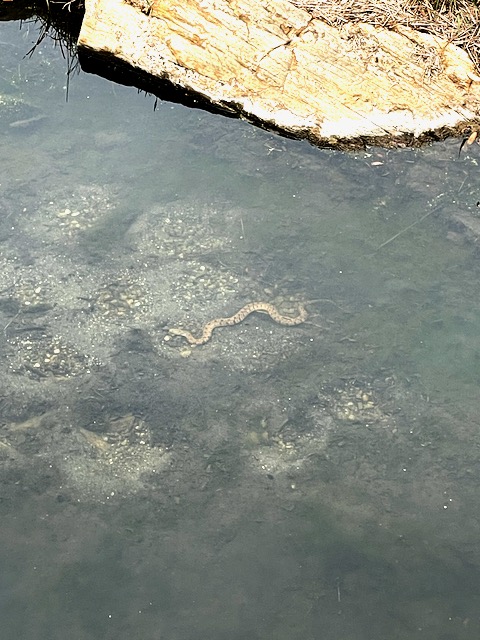

Debbie and were nearing the end of our morning run on Tuesday, crossing the bridge on Bay West Blvd that runs over Dry Branch Creek, and we looked down at the water 20 feet below us. This is what we saw, resting on the creek bottom in about two feet of water.

This is a diamondback water snake (Nerodia rhombifer), a non-venomous aquatic snake that feeds on fish, frogs, toads, and pretty much anything else small enough to ingest. While its bite is not venomous, it does have a reputation as being short-tempered and will bite if handled or harassed…as would most of us.

I cropped the preceding photo and enhanced it a bit to give a better look:

I estimate that the snake was perhaps three feet in length, although it’s difficult to estimate from that distance.

We were pretty excited to see and identify it, as they’re not that common around here. In fact, this is the first one we’ve seen in Horseshoe Bay.

Discover more from The Fire Ant Gazette

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Miss getting out and seeing the flora and fauna. Thanks for the share. Texas is blessed by beautiful cacti, wildflowers and critters. It is clear you and Debbie are getting to know them in central Texas. My life is busy with chickens, pets, and caring for a momma cat (partially feral) and her six baby kittens. Soon the kittens will be vamoosing to their new homes, momma will be fixed and moving on and life in west Texas will go on.

Continuing my prayers for you both.

God bless

Cerise

Every region of our state has something to offer to everyone who is able (or has the discipline) to simply look. It also helps to develop an attitude of wonder about even the most seemingly mundane things. We can enrich our lives by looking past ourselves…even if what we see are chickens! 🤗